Michal Martychowiec

Tears of Iblis. All that is solid melts into air.

‘After all, there is nothing in creation that is not ultimately destined to be lost: not only the part of each and every moment that must be lost and forgotten – the daily squandering of tiny gestures, of minute sensations, of that which passes through the mind in a flash, of trite and wasted words, all of which exceed by great measure the mercy of memory and the archive of redemption – but also the works of art and ingenuity, the fruits of a long and patient labour that, sooner or later, are condemned to disappear. It is over this immemorial mass, over the unformed and immense chaos of what must be lost that, according to the Islamic tradition, Iblis, the angel that has eyes only for the work of creation, cries incessantly.’ Agamben, Creation and salvation. In: Agamben, G. (2010) Nudities. Stanford University Press.

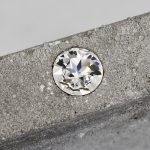

One of the recurring elements in Martychowiec’s practice and this exhibition is glass crystal, originated within the project Sous les pavés, la plage ! The title holds a clear reference to the France’s 1968 student protests (of which it was one of the slogans). ‘Under the cobblestones, the beach’. If the cobblestones were to represent the city and the contemporary civilisation, the sand was to symbolise nature and freedom. In this narrative the crystals replace the sand, bringing us closer to contemporary aesthetics where ‘real’ is not allowed, and can there be a more perfect replacement for sand, if not the crystal which, incidentally, is made of it.

1968 was a breakthrough moment in history, as the civil rights movements failed to prevent the later development of the neo-liberal policies throughout the world resulting in concentration of wealth, decline of the working and middle classes and then perhaps even rise of the right wing sentiment among the populations of the present. Thus the crystal for Martychowiec became the representation of exactly that new age. In the neo-liberal landscape freedom remains but an attractive illusion of what it actually is. In a world where to be is no longer to exercise freedom through acts and thought, but to consume.

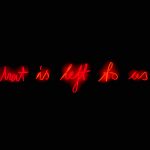

Taken this context into consideration let us look at the works: we are ‘greeted’ by a hand offering a handful of crystals in a tempting fashion. Accompanying this work, we see a neon that reads: What is left to us? This work, as most of Martychowiec neons, functions as a sort of titular entity throughout the exhibition, echoing on the visitor’s head after every individual work he/she might stumble upon.

What is thus left to us? Accepting this artificial and cold beauty of the sparkle while becoming apathetic and passive? Or perhaps…?

In the centre of the space stands a pavement plate with a large crystal embroidered onto the upper edge. Arte povera is a series of sculptures made using pavement plates (as a more contemporary replacement for cobble stones) and crystals. The artistic movement Arte povera’s origin takes place interestingly around the same time as the civil right’s movement and could be said some of their political implications are in line.

On one hand, it would seem the title could be taken quite literally as the ‘poorness’ of this work reflects the generic value of materials it has been made with indeed (glass and concrete). Here, the sparkles of the large crystal attract the spectator, although one might ask, why would such ‘poor’ and common materials attract? These works, on the other hand, offer a certain personal mirroring and questioning of our contemporary condition, in a way typical to Martychowiec. For the spectator might fail to find answer as to why the work attracts. Is it art that is ‘poor’? Or is it that our life has become so? And, once again, if so, what then is left to us?

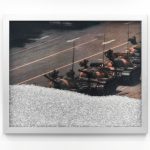

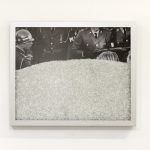

In Sous les pavés, la plage ! (1989), we face an image partially covered with a layer of crystals. The familiar image pictures the nicknamed ‘Tank man’ - an unidentified Chinese man who stood in front of a column of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1989, the day after the Chinese military had suppressed the Tiananmen Square protests. The artist is utilising historical images as representations of an ongoing struggle between freedom of the individual will and the power system. In such way the events from France 1968 become a symbolic representation of something universal and repeated in history.

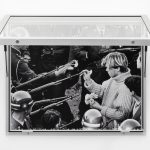

Another similar display, deeper in the gallery, is wide open with 40 000 crystals scattered underneath it on the floor. The image depicts a Vietnam War protester placing a carnation flower into the barrel of an M14 rifle held by a soldier of the 503rd Military Police Battalion in Washington, 1967, an image from which the famous expression ‘flower power’ derives.

Both of these works have the possibility of a twofold presentation. A closed display, with the layer of crystals censoring the historical subversive action, uncomfortable to those in power and deemed preferably forgotten. Wouldn’t it be then better to simply succumb and consume the cold and ‘dead’ beauty of ‘crystal’? After all, if consumption needs are met, is there any need for anything else?

For those holding the key to these displays there is an alternative. Open them, let the crystals pour out underneath and a somewhat different possibility presents itself.

A narrow passage illuminated with the blue light from the neon All is history, gives access to the back room, where a ‘construction’ or a ruin-like area with sand and pavement blocks is presented with a projection behind.

The film The fire and the rose are one is part of a series of films by Martychowiec that investigates and constructs an ongoing reinterpretation of history using symbolic locations, frameworks of historiography, historical, political, and sociological ideologies, and various cultural relics. The film is constructed with two parallel narratives. One is the text of T. S. Elliot’s Four Quartets which suggests on many levels means of reading of the visual part which presents three historically symbolic sites: the former site of Pruitt-Igoe social housing project in St. Louis (representing issues of urban and social planning), the ruins of the Greek village of Levissi located now at the Turkish coast (issues with racial planning), and Ordos City in Inner Mongolia working as a middle point between the other two. The three locations are sort of symbolic historical ruins and each facilitates a new perspective in consideration to our present circumstances.

Tears of Iblis is one of three exhibition cycles curated by Michal Martychowiec with his own works. Each of the three cycles points to specific periods in history and so: What remains the poets provide represents Romanticism and re-establishes certain aspects abandoned in the modern discourse. Tears of Iblis deals directly with the following modernity and destruction of the Icon, and explores cultural development in the modernist West and similarly in the post-Cultural Revolution China. Through Journey to the West the artist presents a complex system within his practice. Various symbolic elements, like the panda, rabbit Josephine, broken glass or glass crystals combine into a cosmos which course runs parallel to our own contemporary world. And it is thus that all works of Martychowiec have a deeply engraved political message.